Anti-Americanism: It’s About American Power, Not Policy

How can America improve its image abroad? Answers to this question are being bandied by all of the presidential hopefuls.

Anti-Americanism: It’s About American Power, Not Policy

Soeren Kern | Grupo de Estudios Estratégicos | December 17, 2007

Hillary Clinton says she would “send a message heard across the world: The era of cowboy diplomacy is over.” John McCain promises to “immediately close Guantanamo Bay.” Ron Paul and Barack Obama both say they would withdraw American troops from Iraq.

Implicit is the notion that George W Bush has tarnished America’s reputation in the world, and that reversing some of his more contentious policies will make the United States popular again. If only it were that simple.

Although polls do indeed show that President Bush has brought anti-Americanism to the surface in many parts of the world, the roots of enmity toward America reach far deeper than one man and his policies. The problem of anti-Americanism will not go away just because Americans elect a new president.

Contrary to much of today’s conventional wisdom, anti-Americanism is not a recent phenomenon. In Europe, for example, anti-Americanism is as old as the United States itself. In fact, anti-Americanism is so established on the Old Continent that there are now as many different brands of anti-Americanism as there are European countries.

Take Spain, for example, where anti-Americanism goes back to the Spanish-American War, which in 1898 drove the final nail into the coffin of the Spanish empire and ended its colonial exploitation of Cuba. Many Spaniards also resent America’s support for General Francisco Franco (1892-1975), who in his day was popular with the Americans because of his strong anti-Communist credentials.

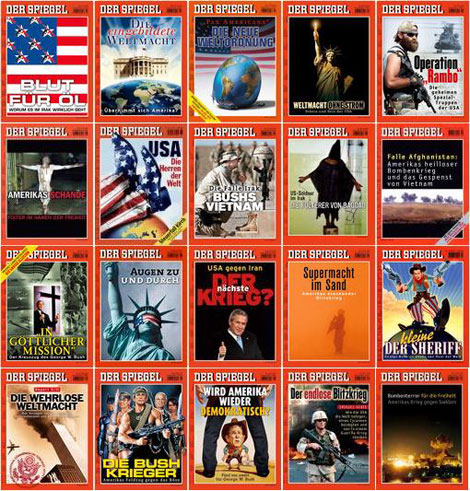

In Germany, anti-Americanism is an exercise in moral relativism. Germans desperately want their country to be perceived as a “normal” country, and its elites are using anti-Americanism as a political tool to absolve themselves and their parents of the crimes of World War II. They routinely equate the US invasion of Iraq with the Holocaust, for example, as a psychological ruse to make themselves feel better about their sordid past.

In France, anti-Americanism is an inferiority complex masquerading as a superiority complex. France is the birthplace of anti-Americanism (the first act of which has been traced to a French lawyer in the late 1700s), and bashing the United States is an inexpensive way to indulge France’s fantasies of past greatness and splendor.

As political realists like Thucydides (c 460-395 BC) might have predicted, anti-Americanism is also a visceral reaction against the current distribution of global power. America commands a level of economic, military and cultural influence that leaves many around the world envious, resentful and even angry and afraid. Indeed, most purveyors of anti-Americanism will continue to bash America until the United States is balanced or replaced (by those same anti-Americans, of course) as the dominant actor on the global stage.

In Europe, for example, where self-referential elites are pathologically obsessed with their perceived need to “counter-balance” the United States, anti-Americanism is now the dominant ideology of public life. In fact, it is no coincidence that the spectacular rise in anti-Americanism in Europe has come at precisely the same time that the European Union, which often struggles to speak with one voice, has been trying to make its political weight felt both at home and abroad.

In their quest to transform Europe into a superpower capable of challenging the United States, European elites are using anti-Americanism to forge a new pan-European identity. This artificial post-modern European “citizenship”, which demands allegiance to a faceless bureaucratic superstate based in Brussels instead of to the traditional nation-state, is being set up in opposition to the United States. To be “European” means (nothing more and nothing less than) to not be an American.

Because European anti-Americanism has much more to do with European identity politics than with genuine opposition to American foreign policy, European elites do not really want the United States to change. Without the intellectual crutch of anti-Americanism, the new “Europe” would lose its raison d’être.

Anti-Americanism also drives Europe’s fixation with its diplomatic and economic “soft power” alternative as the elixir for the world’s problems. Europeans despise America’s military “hard power” because it magnifies the preponderance of US power and influence on the world stage, thereby exposing the fiction behind Europe’s superpower pretensions.

Europeans know they will never achieve hard power parity with America, so they want to change the rules of the international game to make soft power the only acceptable superpower standard. Toward this end, European elites seek to de-legitimize one of the main pillars of American influence by making it prohibitively costly in the realm of international public opinion for the United States to use its military power in the future. By ensconcing a system of international law based around the United Nations, they hope to constrain American exercise of power. For Europeans, multilateralism is about neutering American hard power, not about solving international problems. It is, as the cliché goes, about Lilliputians tying down Gulliver.

Many American foreign policy mavens refuse to recognize this. In fact, they often over-idolize European soft power, largely because they share the European belief that a multilateral world order is the proper antidote to global anti-Americanism.

Case in point is a new report on “smart power” recently released by the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). The document proffers policy advice based on the fiction that the blame for anti-Americanism lies entirely with the United States. It calls on the next president to fix the problem of anti-Americanism by pursuing a neo-liberal norm-based internationalist foreign policy; it argues, predictably, that America can restore its standing in the world by working through the United Nations and by signing the Kyoto Protocol and the International Criminal Court.

But the report says not a word about the gratuitous anti-American bigotry of Europe’s “sophisticated” elites. Nor does it acknowledge that most European purveyors of anti-Americanism are far more opposed to what America is than to what America does. It is not primarily US foreign policy they seek to change: What Europeans (and many of their American converts) want is a wholesale re-creation of America in the post-modern European pacifist image.

To earn the approbation of Europe’s sanctimonious elites, the next American president would (for starters) have to relinquish all use of military force, surrender US sovereignty to the United Nations, adopt a socialist economic model, abolish the death penalty, accept an Iranian nuclear bomb, abandon US support for Israel, appease the Islamic world in a high-minded “Alliance of Civilizations”… and so on.

Anti-Americanism is (at least for the foreseeable future) a zero-sum game because the main purveyors of anti-Americanism are in denial about the dangers facing the world today. They believe the United States is the problem and that their vision for a post-modern socialist multicultural utopia is the solution. Never mind that most Europeans do not have enough faith in their own model to want to pass it on to the next generation.

This is the dilemma America faces: If it wants to be popular abroad, it will have to pay in terms of reduced security. And if it determines to protect the American way of life from global threats, then it will have to pay in terms of reduced popularity abroad.

But if America loses out against the existential threats posed by global terrorism and fundamentalist Islam, then the issue of America’s international image will be moot.

Better, therefore, if the next president focuses on keeping America strong and secure, rather than on pleasing those who will never like the United States, even if its foreign policy is more benign.

Better, also, for the next president to focus on wielding American power wisely, because doing so will earn the United States (grudging) respect, which in the game of unstable relationships that characterizes modern statecraft, is far more important than love.

Soeren Kern is Senior Analyst for Transatlantic Relations at the Madrid-based Grupo de Estudios Estratégicos / Strategic Studies Group

Originally published in American Thinker

Also published in Brussels Journal

Also published in Free Republic