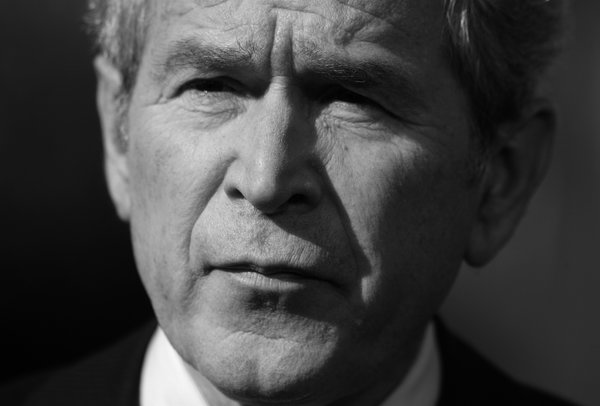

Why Bush Still Matters

In November 2004, George W. Bush became the first Republican president in more than 100 years to be re-elected with majorities in both the House and the Senate.

Why Bush Still Matters

Soeren Kern | Elcano Royal Institute for Strategic and International Studies | January 12, 2006

Summary

In November 2004, George W. Bush became the first Republican president in more than 100 years to be re-elected with majorities in both the House and the Senate. He then claimed a mandate for a bold agenda of initiatives ranging from improving education and healthcare at home to promoting democracy and freedom abroad.

But in what has become an object lesson in the political risks of big thinking, Bush quickly lost momentum, and the first year of his second term was the least successful of his presidency so far.

Some analysts say Bush has been hobbled by a well-established pattern in which almost every second-term president in American history has faced some sort of catastrophe.

Indeed, a series of domestic setbacks has weakened Bush’s leverage over his own party, a situation that has emboldened the opposition. As a result, his capacity to persuade Congress to go along with his agenda has diminished.

With mid-term congressional elections now on the horizon, Bush hopes to steer a mid-course correction by focusing on issues he believes Americans outside Washington care most about: Iraq, immigration and the economy.

Can Bush turn things around? Here history may provide an answer: most modern-day American presidents have been able to recover lost political ground during their second terms.

Analysis

In the heady days after US President George W. Bush was re-elected in November 2004, he claimed a mandate to pursue an aggressive agenda. “I earned capital in the campaign…political capital…and I intend to spend it. It is my style,” he said. The re-energised White House then spelled out a second-term agenda that was audacious in scope.

Domestically, Bush promised to reform Social Security, radically re-write the tax code, change the immigration system and install a conservative judiciary that will long outlive his presidency. Abroad, Bush announced that he would democratise the Middle East, stay the course in Iraq and continue a relentless pursuit of the war on terrorism. Taken together, Bush aimed to overhaul the federal government to bring about long-term Republican domination over US politics and secure long-term US hegemony over the world.

Bush enters 2006 with many of these plans unfulfilled. To be sure, the White House did achieve major successes in 2005: the first national energy legislation in more than a decade, a US$286 billion highway bill to modernise the transport network, a groundbreaking law that limits frivolous lawsuits and the first overhaul of US bankruptcy legislation in a quarter century. Bush also won a free-trade agreement with six countries in Latin America, and made some progress in reshaping the Supreme Court in his own image. Moreover, Congress passed its first budget resolution in years, largely along the lines of Bush’s proposals, and gave him nearly everything he asked for in an US$82 billion supplemental appropriations bill to pay for war costs in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But most of the president’s successes in 2005 were overshadowed by Iraq, the main source of domestic trouble for the White House, and the primary drain of political capital. The rising US death toll in an increasingly unpopular war in Iraq made overarching initiatives “such as restructuring Social Security” unworkable. And plans to rebuild public confidence over Iraq were shattered by the bungled federal response to Hurricane Katrina, as well as the implosion of his nomination of White House counsel Harriet Miers for the Supreme Court. Moreover, allegations of abuse of terror suspects raised disturbing questions about how the war on terror is being waged.

Bush has recently regained his political footing as Americans sense that progress is being made in Iraq. His record-low poll numbers are rebounding, and the next few months will be critical in what the White House hopes will be a turning-point year. Bush will lay out his goals for 2006 in his annual State of the Union address to Congress in late January, and present his spending priorities in the US$2.6 trillion fiscal 2007 budget plan he sends to lawmakers in early February.

Although Bush is unlikely to launch many new initiatives in 2006, he has said his job is “to make a difference, not to mark time”. Indeed, there is still much unfinished business left over from 2005. What follows is a brief summary of what are likely to be the top domestic and foreign issues in American politics during the next twelve months.

Congressional Elections

The mid-term congressional elections scheduled for 7 November will dominate US politics in 2006. With all 435 House members and 33 senators up for election this year, it is entirely possible that Republicans will lose seats in…and maybe even control of…the House or Senate, or both. For Bush, a mid-term election in which Republicans do badly will draw a line of demarcation between a presidency and a lame-duck administration.

Republican anxiety over the mid-term elections will increase tensions between the White House and Congress, which in turn will complicate the president’s domestic agenda. Even in the best of times it is difficult for Congress to get anything done during an election year, as lawmakers turn their attention to re-election campaigns and look out mostly for themselves. Indeed, those Republican members of Congress who are politically vulnerable might seek to distance themselves from a weakened president; some might even be reluctant to have Bush campaign for them in 2006.

Although Bush’s popularity is down, it remains far from certain, however, that the Democrats will achieve major gains in November. Republicans currently hold a 231-203 edge over Democrats in the House of Representatives, with one vacant seat. In the Senate, their advantage is 55-45. Of the 33 Senate seats in play, 15 are held by Republicans. Because Congressional boundary lines place most lawmakers in districts clearly favouring one party or the other, fewer than 10% of House seats held by Republicans currently are considered at risk. And most Senate Republicans facing re-election in 2006 remain favoured to win.

Moreover, although Democrats have sharpened their attacks on Republicans, in practical terms they have been unable to reap meaningful benefits from the political difficulties faced by their opponents. For example, although a high-profile ethics scandal forced the majority leader of the House of Representatives, Tom DeLay, to step down, members of both parties have been accused of violating campaign-finance rules. And although Democrats have accused the Bush Administration of domestic spying without court authorisation, recent polls show that half of Americans say it is an acceptable way to fight terrorism, and two-thirds believe it is more important to investigate possible terrorist threats than to protect civil liberties.

In addition, the Democratic Party itself remains deeply split over whether to pursue a strategy designed to energise its left-leaning base, or to move to the centre in an effort to attract so-called swing voters and make the party more inclusive. Indeed, Democrats currently lack either a single national voice or a clearly defined agenda for voters to seize upon, and many Democrats sound more like Republicans on social issues.

A big challenge for both Democrats and Republicans in 2006 will therefore be to find issues that can shake up the political environment. At the moment, neither party appears quite sure about what to do next. But an old adage says that “a day is a lifetime in American politics”.

Democracy in Iraq

Democracy in Iraq will be the make-or-break issue of Bush’s presidential legacy. Iraq is the dominant issue affecting voters, and according to the latest Gallup poll only about 35% of the American public approves of the way Bush is handling the war effort. Iraq has eclipsed almost every other issue on Capitol Hill, and has slowed or stopped progress on much of Bush’s legislative agenda.

The White House itself is fractured over the war, and is currently facing an internal debate between those aides who are pushing for a withdrawal to relieve domestic political pressure, and others who fear that a premature departure from Iraq would cut short a successful undertaking that will create a large part of Bush’s legacy.

The White House says that 2006 will be “a transitional year” in Iraq, and signs are emerging of a convergence of opinion on how the Bush Administration might begin to exit the conflict. Following a visit to Iraq, on 23 November Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said that the training of Iraqi soldiers had advanced far enough for some of the 160,000 US troops currently in the country probably not being needed much longer. And in a major speech at the US Naval Academy on 30 November, Bush heralded the improved readiness of Iraqi troops, which he has identified as the key condition for reducing the American troop presence in Iraq. Later the same day, the White House released a 35-page document titled “National Strategy for Victory in Iraq”, an unclassified version of its plan to rebuild Iraq.

By laying the groundwork for an accelerated withdrawal of potentially large numbers of US troops from Iraq, the White House appears to be deflecting domestic political pressure ahead of the elections in November. In a move that could help Republican candidates at the polls, the White House is expected to withdraw up to 40,000 US troops from Iraq in 2006. This would be followed by further substantial pullouts in 2007 if Iraqis forces are able to contain the insurgency. The US hopes that by the end of 2007, the remaining US presence in Iraq will be small enough as not to offend Iraqi sensibilities, yet large enough to help Iraq’s military with reconnaissance, intelligence gathering and air power.

At the same time, Bush has said that any reduction in the number of US troops in Iraq will be based on conditions on the ground, not on false political timetables. In fact, major questions remain about the readiness of Iraq’s fledgling security forces. Senior US military commanders told the House Armed Services Committee on 29 September that just one Iraqi battalion, about 700 soldiers, was considered capable of undertaking combat operations fully independent of US support.

Iran, Israel and the Bomb

Even as Bush tries to find a way to bring Iraq to a successful conclusion, a vastly more dangerous conflict with Iran looms just over the horizon. Indeed, Iran constitutes the most pressing foreign policy challenge facing the Bush Administration in 2006.

The White House believes that Iran is trying to develop nuclear weapons under the guise of a civilian nuclear power programme. Tehran insists its atomic programme is for purely peaceful purposes. But it has also admitted to deceiving the International Atomic Energy Agency about the extent of its nuclear activities for more than two decades. The United States has been pushing for a several years to bring the issue to the United Nations Security Council.

Some European leaders have stressed the need for diplomacy over military action. And in public the White House has been careful to express support for the diplomatic initiative being pursued by Britain, France and Germany (EU3), in which Tehran is being pressed to curtail its nuclear ambitions. But privately senior US officials view this diplomatic exercise with the same scepticism as they did the UN process ahead of the invasion of Iraq.

The centre of diplomatic efforts is an agreement the EU3 reached with Iran in November 2004, in which Tehran agreed temporarily to suspend activities related to uranium enrichment. In exchange, Iran was offered a broad package of political and economic incentives, an offer which Tehran has since rejected. The European initiative was further thrown into disarray in January 2006 after Iran resumed those nuclear activities that it had earlier promised to suspend.

As a result, the Europeans have moved closer to the American position. Many European governments now share the American suspicion that Iran is trying to build a nuclear weapon, and that its atomic programme is far more advanced than the Iraqi programme was at its height under Saddam Hussein. Moreover, almost everyone agrees that the chances of containing Iran’s nuclear ambitions through diplomacy are slim. The stage is now set for a dangerous showdown.

Israel is unlikely to accept Iran’s word that its nuclear programme is meant solely for peaceful purposes. In a series of anti-Israel tirades, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran’s new conservative president, said the European attempt to eradicate Jews in the Holocaust was “myth”. He also called for Israel to “be wiped off the map”. His comments increase the likelihood that Israel will take decisive military action to destroy Iranian nuclear facilities if diplomacy ends in failure.

Some reports suggest that Israel has built replicas of Iran’s nuclear facilities in the Negev Desert, where their fighter-bombers have been practicing test runs for months. Israel knows it has a small window of opportunity if it is to take out Iran’s nuclear facilities before it is too late. With leading Democrats accusing Bush of “outsourcing” US foreign policy to Europe, the White House faces increasing pressure to act decisively.

The strategic usefulness of a unilateral preventive attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities would probably be short lived. Given the sophisticated nature of Iranian capabilities, even if its main facilities were to be destroyed, Iran has the know-how to pursue a more vigorous nuclear weapons programme over the long term. But White House advisors may conclude that the political fallout from an Israeli raid would be catastrophic. Therefore, they may decide that an American strike is their best worst option, in the hope of at least delaying the emergence of an Iranian nuclear bomb.

United Nations Reform

The Bush Administration’s main priority at the United Nations during 2006 will be to find an acceptable replacement for outgoing Secretary General Kofi Annan. Indeed, with more than a dozen candidates, the race to succeed Annan, whose second five-year term runs through the end of December 2006, is already in high gear.

But the winner of what is set to become one of the fiercest succession battles in UN history will be largely determined by the United States. There are no specific qualifications for secretary general, but American officials say they are looking for a strong administrator to implement reforms the White House says are needed to make the UN more effective at solving problems. If the UN does not become more responsive to US concerns, Washington says it will seek other venues like NATO or the Red Cross for international action. Republican lawmakers have already threatened to withhold half of America’s contributions to the UN’s 2006 budget.

John Bolton, the US envoy to the UN, says the White House wants to settle on a successor by July, and American diplomats are already “pre-screening” potential candidates. This has led to speculation that Annan may step down several months early so that his successor can take over before the next session of the General Assembly in September.

Based on the informal practice of rotation among the UN’s main regional groupings, Asian countries say it is their turn to hold the top job. Although a number of Asian candidates have already emerged, neither individual has generated much enthusiasm abroad. Moreover, Asia is politically fractured, and the continent may find it difficult to reach an agreement on fielding a single candidate. In any case, many countries are sceptical about the idea of geographical rotation, and Bolton says he does not believe “the next Secretary General belongs to any particular region”.

Indeed, newly independent Eastern European countries are also claiming the post in recognition of their emergence as democracies from Soviet domination. And the most serious non-Asian candidate at the moment is Aleksander Kwasniewski, the former Polish president. A former left-wing politician who spearheaded the expansion of NATO and became a firm US ally in the war on terrorism, Kwasniewski has powerful supporters in the White House.

Another unwritten rule holds that the Secretary General should not come from one of the five permanent member countries of the Security Council. But the selection process this time around will not follow the usual formulas. If the decision reflects where the real power lies in the world body, then perhaps former US President Bill Clinton may become the world’s top civil servant.

Immigration Reform

Bush has made immigration reform a top item on his domestic agenda. But few issues in American politics are more contentious, even within the president’s own party. The debate over fixing the immigration system, which has defied effective solutions for over three decades, is expected to play a major role in elections in many states in 2006.

There are an estimated 11 million illegal immigrants in the United States, mostly from Latin America, and over the past five years that number has been growing exponentially by about one million annually. Bush, who favours a more open immigration policy, is pushing for a carrot-and-stick approach to dealing with illegal immigrants that will satisfy his conservative base “without alienating Hispanic voters, the nation’s fastest-growing voting bloc”.

A key element of the Bush proposal is a guest-worker plan that would not only allow foreign workers into the United States under temporary work visas, but would also legalise the status of those illegal immigrants already in the country. Moreover, most Democrats support the president’s guest-worker programme. But many Republicans say Bush is being too lenient.

In fact, the Republican Party is deeply divided between moderate lawmakers who support Bush’s guest-worker programme for non-citizens, and others demanding a strict crackdown on illegal immigration. Many conservative opponents of the White House proposal are hostile to illegal immigrants and want them deported; such critics argue that the president’s plan is in reality an amnesty because it would accept people who entered the United States by breaking the law. Bowing to such pressure, the White House has already dropped a provision that would offer such temporary workers a path towards permanent legal status.

The US business community, a traditional ally of the Republican Party, is pushing for more liberal immigration laws that would augment the supply of cheap labour. The US Chamber of Commerce, the most powerful business lobby in the country, says that with the national unemployment rate close to historic lows, and 77 million baby boomers preparing to leave the workforce, American companies cannot find enough workers.

But many lawmakers are under pressure from their constituents to demonstrate a new resolve before the mid-term elections. An opinion poll taken in mid-December found that four in five Americans think the government is not doing enough to prevent illegal immigration, and only 33% said they approve of how Bush is handling the issue. (But in a reflection of conflicting attitudes, the same poll found that three in five Americans said undocumented workers already in the country should be given the opportunity to stay and become citizens.)

The House of Representatives is pushing for a more hard-line approach, which calls for detaining all illegal immigrants apprehended at the border, and for streamlining deportation processes. The House is also pushing for stiff criminal penalties for those who smuggle immigrants across the border and for new mandatory sentences for immigrants who re-enter illegally after deportation.

Moreover, Congress has approved a plan that would allocate more than US$2.2 billion to build five double-layer border fences totalling more than 1,000 kilometres in Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas. At US$2.2 million a kilometre, the barriers, which are also directed at illegal drug trafficking, would include two layers of reinforced fencing, cameras, lighting and sensors along the most porous corridors of the US border with Mexico.

The immigration issue has created unusual political coalitions that cut across party lines. Business and organised labour are joined together on one side in support of a more flexible immigration system, while conservatives and working class voters are taking a tougher stance. And at the same time, Democrats and Republicans are both battling for Hispanic voters. This will make compromise difficult, if not impossible.

Economic Performance

By almost all measures, 2005 was a very good year for the US economy. The economy expanded by about 3.6% in 2005, the fourth consecutive year of solid growth. The labour market generated two million new jobs in 2005, about the same as in 2004, and in December the unemployment rate fell to 4.9%. Some analysts say job growth would have reached at least 2.2 million had it not been for Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, which destroyed a major American port city and displaced more than one million people.

Prospects for the US economy in 2006 are also bright, with growth forecasts ranging from 3.5% to 3.7% for the year as a whole. Inflation is expected to remain steady, with the core consumer price index (excluding food and energy) rising about 2.1%. The pace of job growth is expected to continue at about 200,000 new jobs per month, and consumer spending is forecast to rise at a healthy clip. In a sign that points to the renewed confidence of investors, the Dow Jones industrial average, a major stock market index, closed above 11,000 points in January 2006 for the first time in almost five years.

The healthy economic data are a well-timed boost for Bush, who has been trying to convince a sceptical American public that his tax and budget policies are working. Indeed, the economic picture now is far brighter than it was during much of his first term in office, a record Bush will now try to leverage to promote his agenda of tax cuts, tighter limits on government spending and more trade.

But Bush’s ability to offer new initiatives is constrained by his goal of cutting the deficit in half as a percentage of gross domestic product by the time he leaves office in early 2009. The official federal budget deficit was US$319 billion in fiscal 2005, down from US$412 billion the previous year. The administration’s goal is a deficit of no more than US$260 billion by 2009.

Moreover, polls show that many Americans are still uneasy about the economy. And critics say Bush has avoided addressing some of the biggest challenges facing the economy, including the slowing down of the housing market, the surge in energy prices and the potentially long-term destabilising effect of the nation’s growing foreign indebtedness.

Many economists believe that a softening of the housing market could slow down the overall pace of growth. Over the past five years, real-estate wealth has driven consumer spending, which makes up 70% of the economy. Some analysts estimate that the housing boom has been responsible for creating up to one million new jobs since 2000. But as home sales begin to slow down, house prices may decline, causing consumers to rein in their spending. That may cause a slowdown in economic growth.

Adding to the unease, Alan Greenspan will step down after 18 years as chairman of the Federal Reserve. He leaves behind a legacy of price stability and “full employment”, the two main policy goals articulated in the Federal Reserve Act. He also enhanced the stability of the American economy through an effective communication strategy that increased transparency about US monetary policy.

Ben Bernanke, who has been nominated to succeed Greenspan, has big shoes to fill. Economists say he could be tested by a number of potential financial emergencies, including housing, energy, hedge fund and debt crises, early in his term. How he responds to these or other unforeseen problems will determine how successful he will be as the world’s top central banker.

Conclusion

The White House lost considerable traction in 2005, and it now faces a daunting challenge to reclaim political capital ahead of mid-term elections in November 2006. Bush is generally viewed by most Americans as a strong and decisive leader, even by many who disagree with him. If Bush regains control of his agenda, his political fortunes will be restored. This implies that on key issues he will still get his way, both at home and abroad.

Soeren Kern

Senior Analyst, United States and Transatlantic Relations, Elcano Royal Institute for Strategic and International Studies