Spain Rethinks Universal Jurisdiction

Lawmakers from Spain’s ruling center-right Popular Party have submitted a bill that would limit the conditions under which Spanish judges can investigate genocide or crimes against humanity committed outside the borders of Spain.

Spain Rethinks Universal Jurisdiction

Soeren Kern | Gatestone Institute | January 31, 2014

Lawmakers from Spain’s ruling center-right Popular Party have submitted a bill that would limit the conditions under which Spanish judges can investigate genocide or crimes against humanity committed outside the borders of Spain.

The move—which comes just weeks after a Spanish judge issued arrest warrants for five high-ranking Chinese officials over alleged human rights abuses in Tibet—would restrict the reach of Spain’s law on universal jurisdiction only to those cases directly involving Spanish citizens or foreign nationals habitually resident in Spain.

Universal jurisdiction is a legal concept whereby states can claim criminal jurisdiction over persons whose alleged crimes were committed outside the boundaries of the prosecuting state, regardless of nationality, country of residence, or any other relation with the prosecuting country.

Spanish judges have gained a reputation for activism in recent years by using the principle of universal jurisdiction to pursue cases against suspected human rights violators overseas, most famously the former Chilean dictator, General Augusto Pinochet.

Spanish magistrates have pursued more than a dozen international investigations into suspected cases of torture, genocide and crimes against humanity, in places as far-flung as Gaza, Guatemala, Iraq and Rwanda. But many of these cases have little or no connection with Spain, and critics say the judges are interpreting the concept of universal jurisdiction too loosely.

Calls to restrict the scope of universal jurisdiction reached a crescendo in 2009 when Spanish magistrates announced highly politicized probes involving Israel and the United States. In January of that year, Spanish Judge Fernando Andreu said he would probe seven top Israeli military and government officials for alleged “crimes against humanity” in the 2002 targeted assassination of Salah Shehadeh, the commander of the military wing of Hamas.

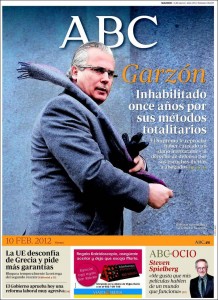

In March 2009, Baltasar Garzón, Spain’s most high-profile judge at the time, invoked the principle of universal jurisdiction to investigate six former Bush administration officials for allegedly giving legal cover to torture committed at the U.S. detention center in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

And in May 2009, another Spanish judge, Santiago Pedraz, said he would charge three U.S. soldiers with crimes against humanity for the April 2003 deaths of a Spanish television cameraman and a Ukrainian journalist. The men were killed when a U.S. tank crew shelled their Baghdad hotel.

The legal standoff came to a head after Andreu rejected requests by Spanish prosecutors to suspend the lawsuit against Israel because Israel was already investigating the case. Several days later, Pedraz said he would continue to pursue his case against the American GIs, even though a National Criminal Court panel, as well as a U.S. Army investigation, recommended that no action be taken.

At the time, Spain’s then Attorney General, Cándido Conde-Pumpido, asked Garzón to shelve his case against the Americans and warned of the risks of turning the Spanish justice system into a “plaything” for politically motivated prosecutions. Garzón ignored that advice and launched yet another investigation seeking information on individuals responsible for the alleged torture of four inmates at Guantánamo. (Garzón has since been disbarred for overstepping his authority.)

Worried that Spain’s judicial system was being hijacked by activist judges pursuing a political agenda, Spanish lawmakers in the Congress of Deputies (lower house) voted in June 2009 to restrict the future scope of universal jurisdiction to cases in which: a) the victims are Spanish; b) the alleged perpetrators are in Spain; or c) there exists some other clear link to Spanish interests. That bill was approved by the Spanish Senate in October 2009 and became law in November 2009.

Despite these restrictions, Spanish judges have not lost their fervor for pursuing high-profile human rights cases based on the concept of universal jurisdiction.

In October 2013, Spanish High Court Judge Ismael Moreno indicted former Chinese President Hu Jintao, 71, for allegedly committing genocide in Tibet, an autonomous region in southwestern China. Moreno said he was competent to rule in the case, which was brought by two Spanish pro-Tibet groups, because one of the activists, Tibetan monk Thubten Wangchen, is a Spanish citizen.

In their lawsuit against Hu Jintao, the Madrid-based Tibetan Support Committee (Comité de Apoyo al Tibet) and the Barcelona-based Tibet House Foundation (Fundació Casa del Tibet) allege that, as Communist leader, he was ultimately responsible for actions “aimed at eliminating the uniqueness and existence of Tibet as a country, imposing martial law, carrying out forced deportations, mass sterilization campaigns and torture of dissidents.”

In November 2013, Moreno issued an arrest warrant for former Chinese President Jiang Zemin, 87, and former Prime Minister Li Peng, 85, as well as three other former high-ranking Chinese officials, over allegations they too committed genocide in Tibet. Moreno said there was sufficient evidence against the five officials to have them appear for questioning in a Spanish court.

The arrest warrants mean the individuals could be detained when they travel to Spain or any other country that has an extradition treaty with Spain.

Chinese officials have—naturally—reacted with anger over Spain’s judicial grandstanding. In comments published by the Reuters news agency, a senior Chinese parliamentary official named Zhu Weiqun said Moreno’s ruling was “absurd” and added: “If some country’s court takes on this matter, it will bring itself enormous embarrassment. Go ahead if you dare.”

The Madrid-based newspaper El País published a warning by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei, who said: “We urge Spain to face up to China’s solemn position, change the wrong decision, repair the severe damage, and refrain from sending wrong signals to the Tibetan independence forces and hurting China-Spain relations.”

By going after China, however, Spain appears to have bitten off more than it can chew. Spain—where 5.9 million people (or 26% of the working population) are currently unemployed, and where the economy contracted by 1.3% in 2013—seems poorly placed to confront China, the world’s second-largest economy.

According to El País Madrid fears Beijing will take economic reprisals against Spain, as it did against Norway after the Norwegian Nobel Committee in 2010 awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, a dissident serving an 11-year prison term in China. More than three years later, there are still no high-level exchanges between China and Norway.

China is Spain’s biggest trading partner outside the European Union, with bilateral trade amounting to $27.6 billion in 2012. China is also the second largest foreign holder of Spanish debt, with about €80 billion ($110 billion), or 20% of the total. In addition, China is an important source of tourists for Spain. More than 175,000 Chinese tourists visited Spain in 2012, a 55% jump over 2011.

Not surprisingly, the government of Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy is seeking to avoid a full-blown crisis in relations with China.

In this context, Spanish lawmakers on January 17 submitted a bill that calls for changes to Spain’s 1985 Organic Law of the Judiciary (Ley Orgánica del Poder Judicial) that would further restrict the application of universal jurisdiction.

In addition to the requirement (established in 2009) that Spanish judges can only pursue crimes of genocide or crimes against humanity when the case directly involves Spanish citizens, the new bill would further require that those individuals who are criminally responsible for the alleged human rights abuses must themselves be Spanish citizens or foreign nationals who obtained their Spanish citizenship before the crimes took place.

The bill also includes a provision that all universal jurisdiction cases pending at the time of the entry into force of the new law should be dismissed if they do not meet the new legal requirements. This would effectively nullify the lawsuit against the Chinese officials.

By reining in the freewheeling judges, Spanish lawmakers are seeking to avert a crisis in relations with China. But they also seem to be heeding the advice of Henry Kissinger, who once warned that “universal jurisdiction risks creating universal tyranny—that of judges.”

Soeren Kern is a Senior Fellow at the New York-based Gatestone Institute. He is also Senior Fellow for European Politics at the Madrid-based Grupo de Estudios Estratégicos / Strategic Studies Group. Follow him on Facebook. Follow him on Twitter.

Link to Original Article: http://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/4149/spain-universal-jurisdiction